Current Research

Past Research

High Performance Computing and Astrophysics

Modern super-computers represent a vast potential tool for testing our understanding of the physical world. They also present a challenging technical problem. Computer programs written for execution on these machines need to be efficient, scalable, flexible and at the same time user friendly. Capturing the best of all these worlds is a challenge faced by researchers in all major institutions.

There are many buzz-words used when describing the goal of such programs, e.g. Exascale or Massively parallel, but what these essentially describe is a codes ability to run utilising a large number of threads while at the same time retaining efficient execution, otherwise known as scalability. This is most commonly achieved by designing a code with a hybrid-parallelisation scheme. This effectively attempts to reduce the volume of communications between the distributed memory locations throughout a super-computer by directing the majority of the communications via the shared memory within a node. Today there exists multiple frameworks for achieving the above goal. My work only makes use of one, the the Kokkos framework.

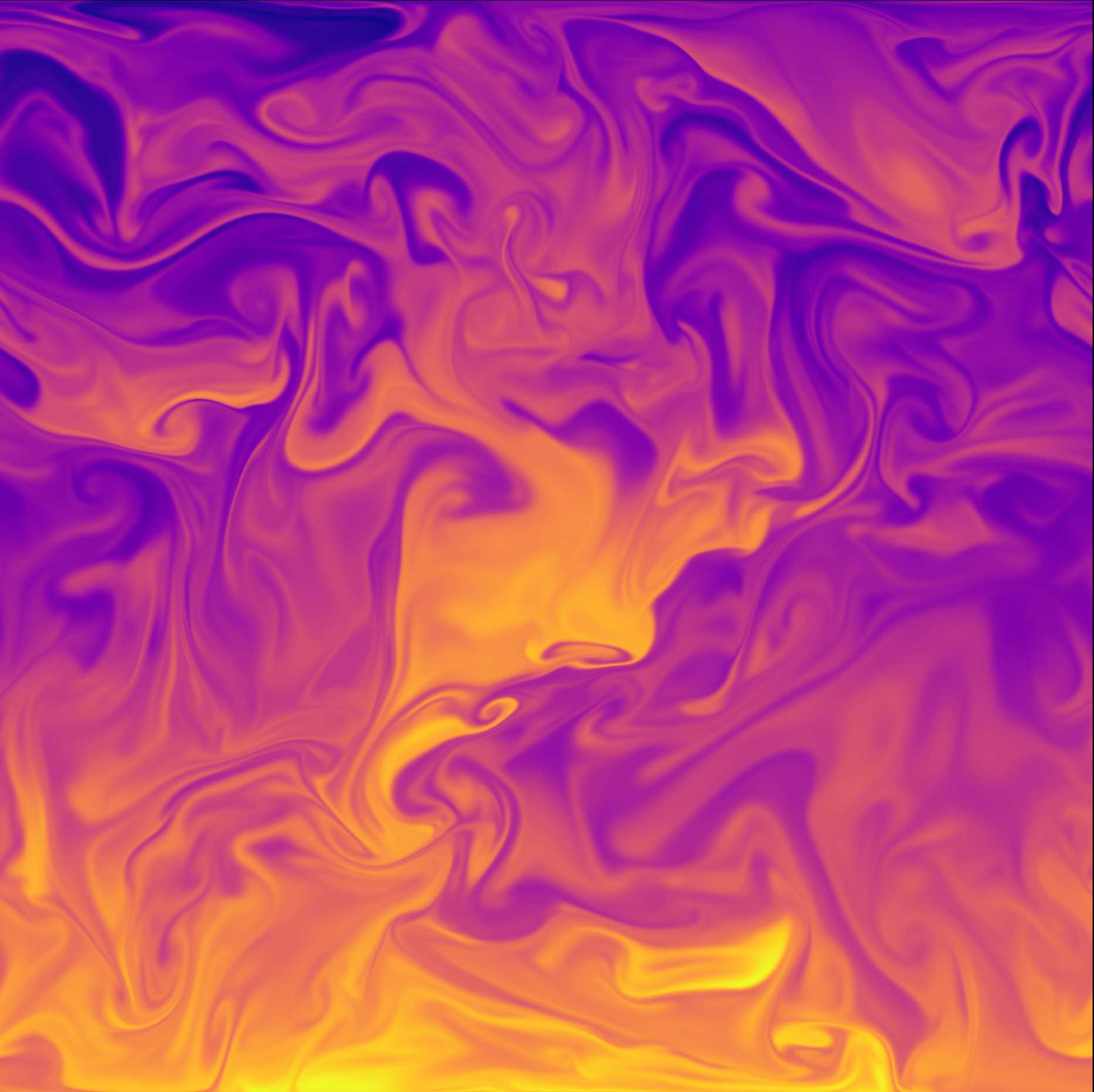

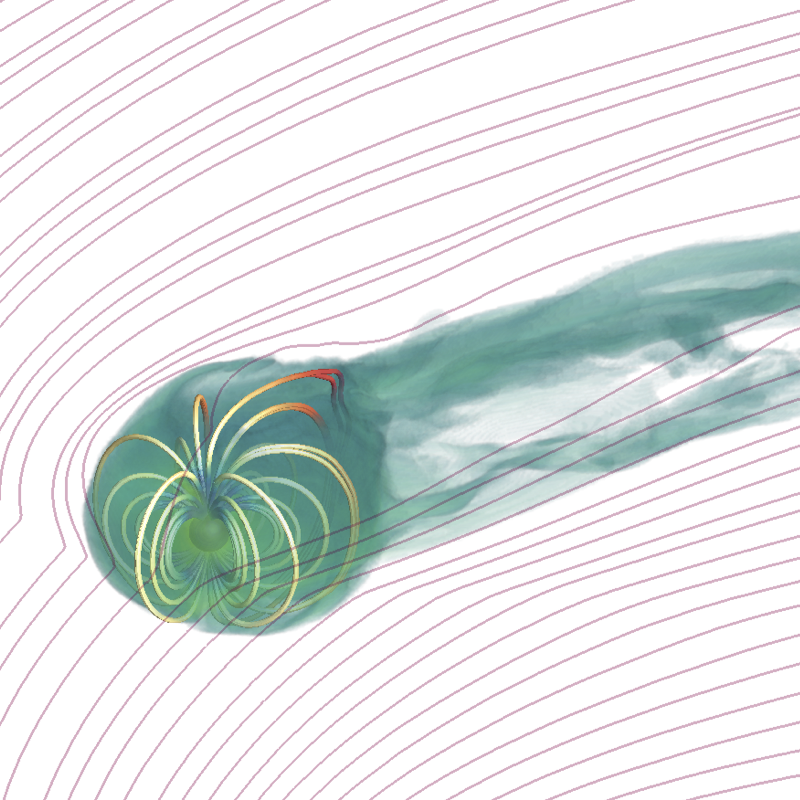

The above image is a rendering of the results of a atmospheric convection simulation. The resolution of the simulation was 50003 grid cells. Each simulation snapshot is 5.2 TB of data. This scale of numerical simulation and data output is not possible without high performance frameworks such as Kokkos or Big Data management methods.

Stars and Planets

Throughout their lifetimes, stars and their planets form a closely bound, highly evolving system driven by a large range of simultaneous physical processes. The aim of my research so far has been to understand the role magnetic fields play in shaping the environment around stars and planets, in order to understand how stars form connections with their planets, the interstellar medium (ISM) and each other.

Magnetic fields are an innate property of stellar and planetary bodies on all length scales, from small surface features to extended winds. The question of what fundamental role magnetic fields play in shaping the environment around stars and planet is central to understanding stellar and planetary formation and evolution, as well as properties of large scale structures such as the ISM, star clusters and beyond.

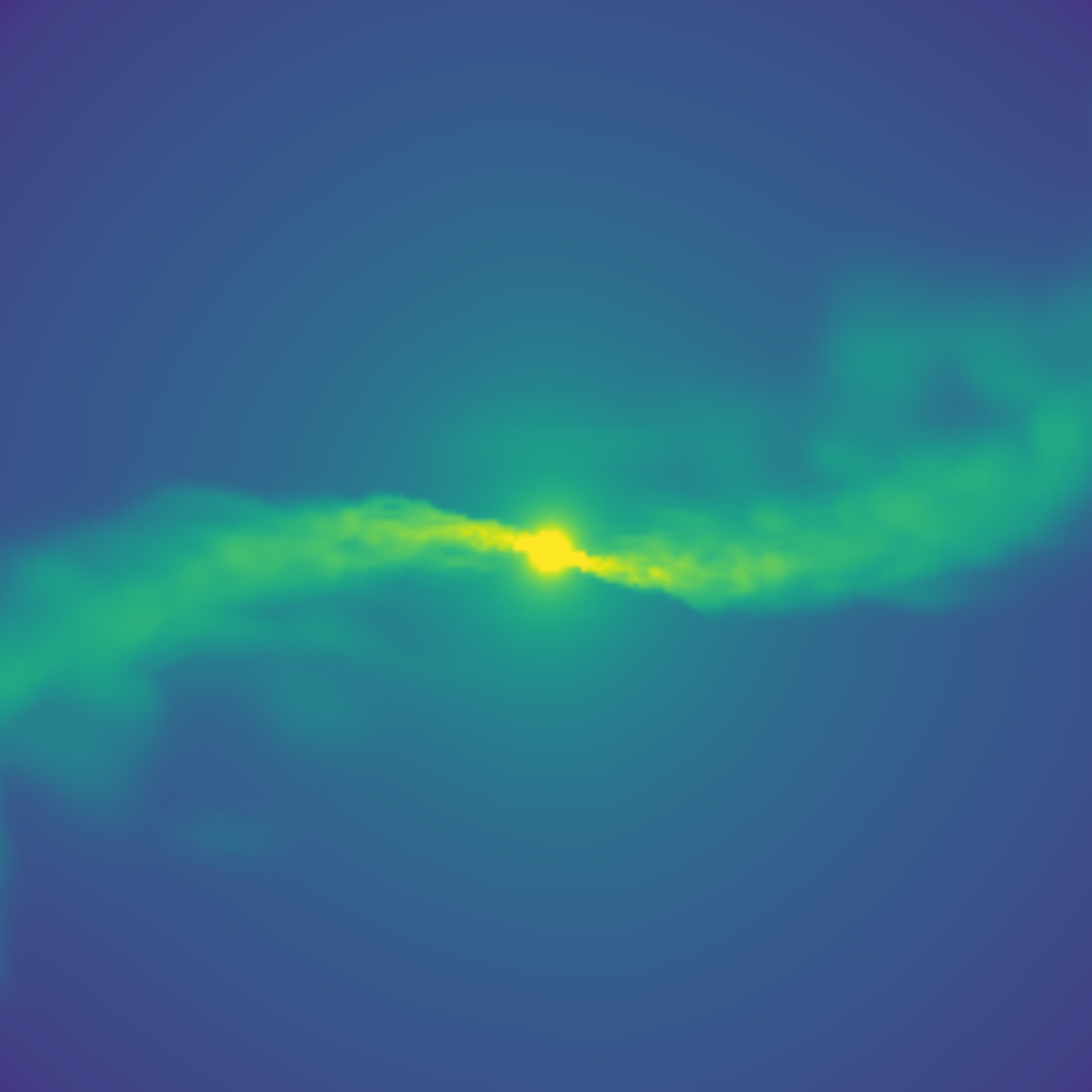

My work to date has been concerned with the winds and environment of main sequence stars, and end of life Jupiter-type exoplanets. Using simulations as numerical experiments, I am able to predict observational signatures of stellar and planetary (co)evolution models to support current and future observational campaigns.Radio emission from stars and planets is an extremely powerful diagnostic tool for testing theoretical models. Thermal emission due to hot plasma and cyclotron emission from magnetically confined electrons occur in many stellar and planetary phenomena. From my simulation results, I predict radio fluxes to directly test my models against observation.

Winds from Massive Stars

Large stars with masses typically above 5 solar masses have winds driven by the intense radiation they produce. As massive stars can be 10,000s of times more luminous than the Sun, these winds can reach velocities in the region of 3000 km/s (much faster than the solar wind of our Sun). Massive stars make up approximately 0.003% of all stars. They are rear but they

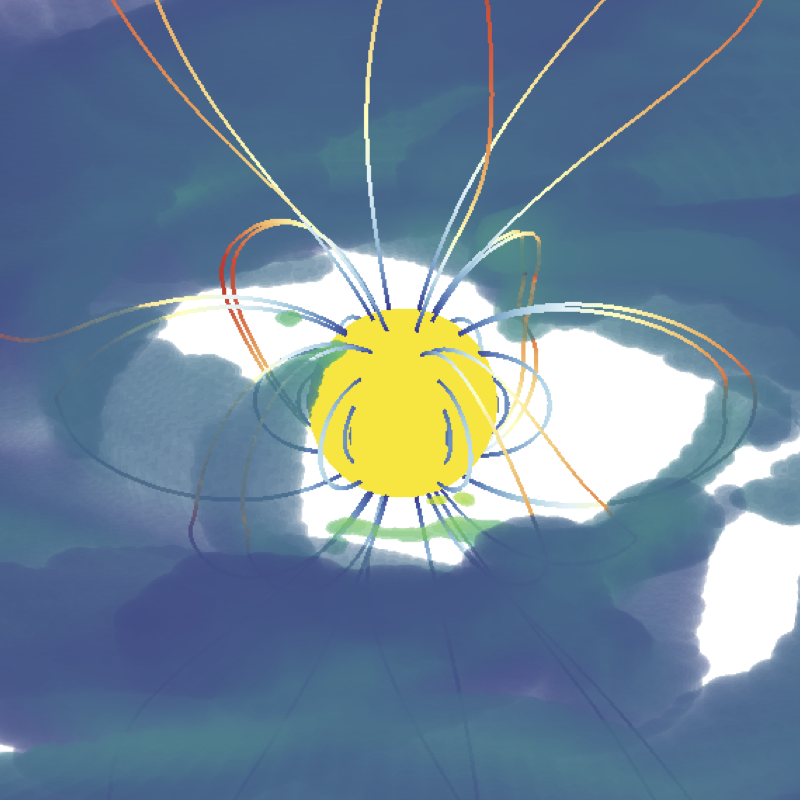

Central is the role of the star's magnetic field, which controls the topology of the expanding stellar wind. This impact can be observed at radio wave lengths, providing insight into the dynamic environment close to the stellar surface. The image to the left is an example of one of my numerical simulations. The star is central with the extended structures representing iso-density contours. About 10% of massive stars are found to be detectably magnetic.

Massive stars are the birth places of elements. The extreme temperatures and pressures at their harts allow for fusion reactions so energetic that the collisions lead to heavy elements; the heaviest of which is Iron (which has the maximum atomic binding energy). Elements weighing more than Iron require cataclysmic events to form. A massive star ends it's life in a massive explosion known as a supernova. Starved of fuel, the star is no longer able to support it's own weight against gravity. Imploding, bouncing and exploding, in an event which constitutes the single most energetic event a galaxy will see; the flux of neutrons leads to neutron-neutron capture. Overcoming the inter-nuclear forces this proses creates heavy elements such as Uranium. Elements found on Earth heavier than Iron were created in similar environments.

Star-Planet Interactions

Closer to home, solar like stars, meaning stars similar to our Sun, also posses magnetic fields. These can be just as strong as those found in their massive counterparts but are much more ubiquitous. Stars with masses ranging from the dimmest red-dwarfs up to A-type stars have all been found to posses magnetic fields to some extent; in contrast to their massive counterparts. host planets similar to those found in our solar system are.

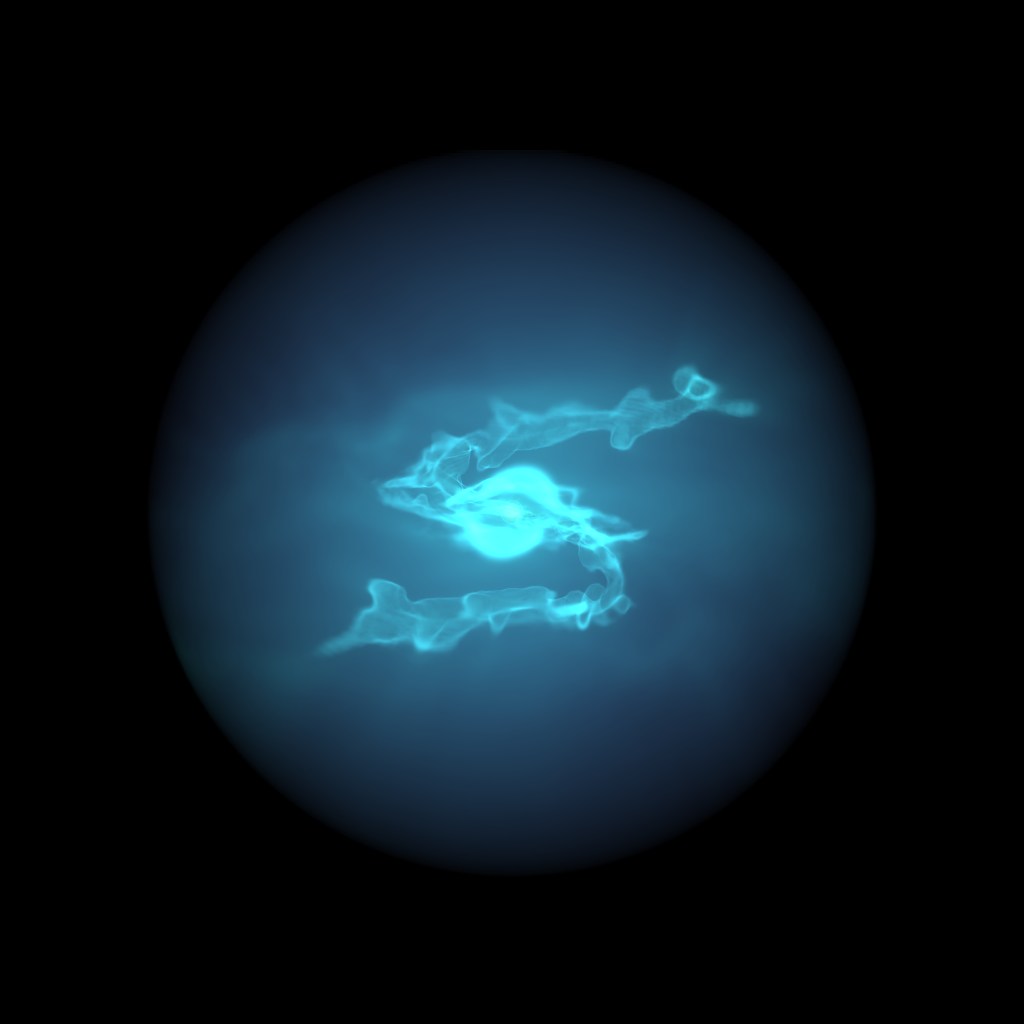

Below are links to videos of MHD simulations of a solar types star with an orbiting planetary body comparable to that of Jupiter. Both the star and planet are magnetised with dipole fields of 1 G. The winds of both the star and planet are initialised according to Parkers wind model.